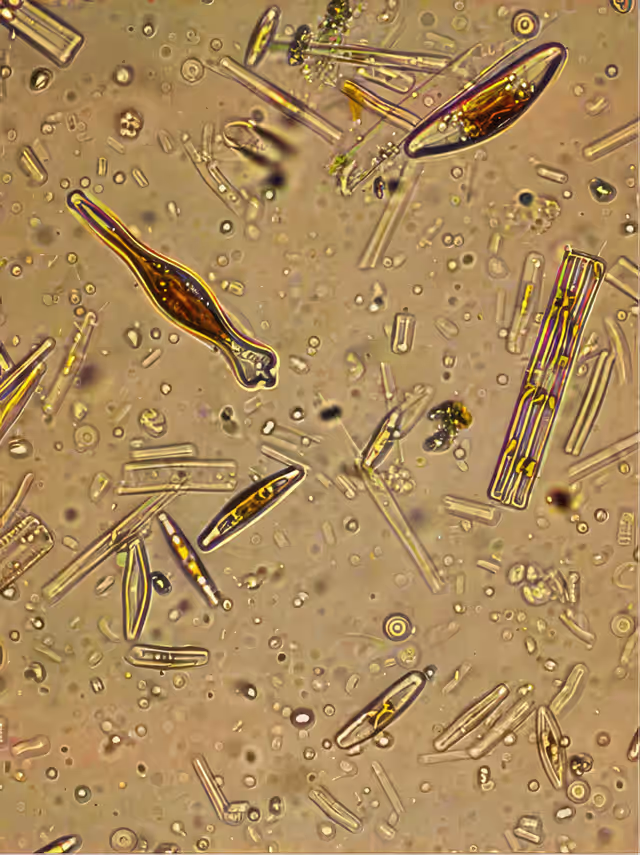

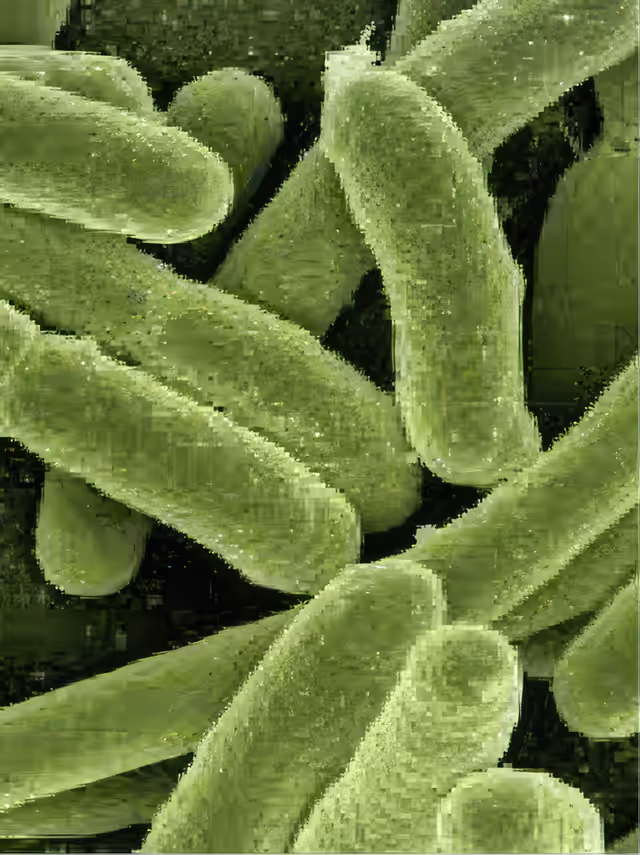

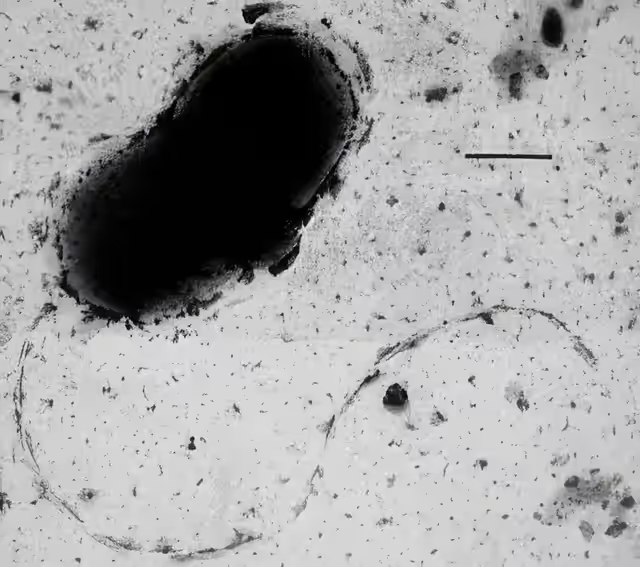

This transition zone is the chemocline, the boundary where oxygen from above disappears and hydrogen sulfide rising from the bottom begins to appear. It is a stable environment with very little light, no oxygen, and abundant sulfur compounds: perfect conditions for an ancient microbial community.

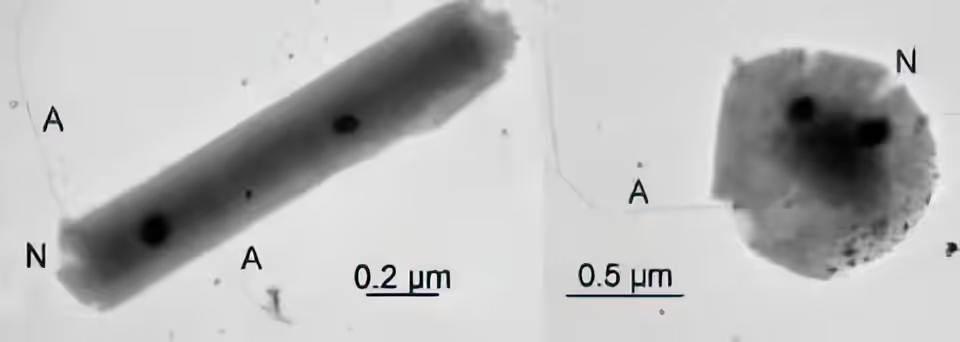

Descending below the chemocline, light vanishes completely and the lake enters its most stable and ancient layer: the monimolimnion. Here the water is dense, saline, and completely oxygen-free. Nothing mixes with what lies above, and every change happens extremely slowly. In this total darkness, organisms survive without oxygen. Among the key actors are sulfate-reducing bacteria, which use sulfate to obtain energy and release hydrogen sulfide. This hydrogen sulfide feeds chemocline bacteria, closing one of the oldest biochemical cycles on Earth: the sulfur cycle. The monimolimnion is therefore an environment dominated by anaerobic processes, the same that characterized primordial oceans long before Earth's atmosphere became oxygen-rich. Here life follows different rules: slower and older. It is a biological archive preserving ways of life from billions of years ago, still fully functioning today in this isolated equilibrium.

It is a silent, closed world suspended in darkness: a living testimony of what Earth may have looked like before photosynthesis changed the planet's history forever.